Source: Kirschner, P. A., & Van Merriënboer, J. (2013). Do learners really know best? Urban legends in Education. Educational Psychologist, 48(3), 169-183.

Criteria for Selection: Peer reviewed. Offers a critical analysis of myths in education and clear action steps for incorporating more evidence-based rhetoric.

LEARN Brief and Infographic Credits: Dr. Marshall Jones, Dr. Jeannie Haubert

Overview:

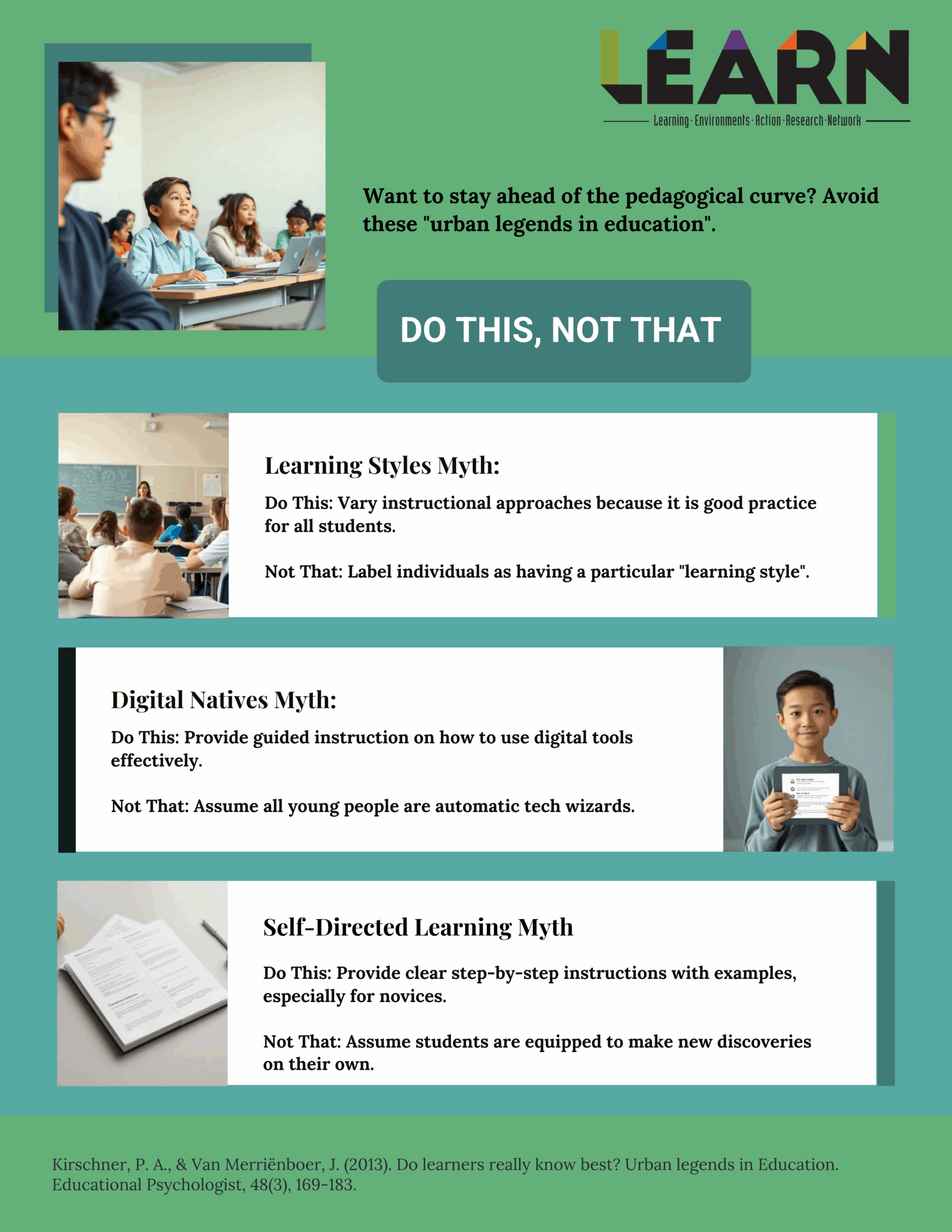

This piece challenges several widely held but unsupported beliefs about learning. It is essential to teacher development that we undo these old ways of thinking and recognize that all students benefit from incorporating evidence-based pedagogical approaches. The authors critique three key myths: that students are “digital natives” naturally adept at using technology, that learners benefit most from instruction tailored to their personal “learning styles”, and that students can effectively direct their own education without substantial support. These misconceptions, the authors argue, often misguide educational practice and policy, detracting from methods that are grounded in cognitive science and proven instructional design.

In response to these myths, the article recommends practical, evidence-based strategies for educators and the districts that support their development. First, instructors should not assume technological fluency in students based on age, but instead offer direct instruction on the purposeful use of digital tools for learning. Secondly, tailoring teaching to perceived learning styles lacks empirical support and should be replaced by more reliable strategies, such as clear explanations, worked examples, and structured practice with feedback. These approaches have consistently been shown to improve comprehension and retention across learner populations. The concept of Learning Styles can be a useful metaphor to help remind us to vary our instructional strategies. Learning Styles as a metaphor can be a helpful gateway to more actionable strategies such as Universal Designs for Learning.

Lastly, the authors emphasize the importance of guided instruction and scaffolding, especially for novice learners. Self-directed learning skills must be explicitly taught and gradually developed, not assumed. Instruction should be structured and sequenced, using models like the Four-Component Instructional Design (4C/ID) to help learners tackle complex tasks in manageable steps. Educators are encouraged to base their practices on cognitive science principles, such as managing cognitive load, rather than on popular but unsubstantiated educational trends.

Key Insights:

1. Avoid Adapting Instruction to “Digital Natives”

Do not assume students are inherently skilled at using technology for learning just because they grew up with it. Instead, provide explicit instruction on how to use digital tools effectively for educational purposes.

2. Avoid Using the Term Learning Styles

Avoid using the phrase “learning styles” in professional development and lesson planning. Instead, focus on varying information presentation strategies, instructional strategies, and assessment methods to engage a wide range of interests. The concepts of Universal Designs for Learning (UDL) may be of use here.

3. Use Structured, Guided Instruction

Prioritize guided instruction, especially for novices, over minimally guided or discovery-based approaches. Consider cognitive load theory as it applies to learners expected to do self-discovery.

4. Base Teaching on Cognitive Science Principles

Rely on principles from cognitive psychology, such as cognitive load theory, rather than educational fads or unproven trends.

Full Study:

Action Step: